Previously I wrote a little tongue in cheek piece about May being National Inventor Month and a brief excerpt on my experience as an inventor.

This time, however, I would like to take a little different and more serious approach to the topic of inventions and inventing, and briefly describe my journey in the process of inventing the Safety Shield, a medical device designed for the prevention of needle sticks.

As a breast imaging radiologist, I was often working and operating in low light conditions during procedures. But why would someone want to do that, you ask? The answer lies in the fact that most of the procedures such as cyst aspirations, breast biopsies, and needle/wire localizations were performed using ultrasound as the guiding imaging modality of choice. Ultrasound technology and its images are used to find and visualize a region of interest, whatever it may be. Seeing and finding what are often very small and subtle or vague objects is optimized by viewing the ultrasound screen in the dark or with low light conditions. This helps the eyes with contrast and resolution of the targeted objects or findings. In essence, “things” are seen better this way and it is akin to watching television or a movie in a darkened room or theater.

So a problem then arises when doing a medical procedure. One would like to have maximum or optimal light when dealing with very sharp instruments required for a procedure such as a biopsy. Those instruments would include several sizes and lengths of needles for superficial and deep anesthesia, a scalpel, and the biopsy device which is sharp and has tissue cutting, capturing, and procurement properties. All of these are dangerous and potential injurious devices; although necessary tools to accomplish the task at hand. But as I wrote before, low light conditions or degrees of darkness are often needed for optimal target visualization. The optimal placement of the needles or the biopsy device helps to provide the best chance to ensure a successful procedure from start to finish. Often times the placement is critical due to nearby nerves, arteries, veins, implants, lungs, or other important or vital structures.

Some of the time each of these demands can be met separately and individually; and at other times they are joined together. The majority of time, however, when the needles and biopsy device are being used and deployed into the body, the lights are dimmed to allow the needed visualization for accurate targeting. Most often the procedure is completed without difficulty or complication.

However, not infrequently, circumstances and situations arise that require adjustments in the technique, a change in needles or instruments, or additional medications applied to the situation or given to the patient. Occasionally, it is this additional medication part where things can get a little dicey, particularly if the lighting conditions are optimized for image visualization and not for other things like drawing up or transferring medications from a bottle into a syringe. For the sake of safety during that task, the lighting would ideally be bright since sharp needles are involved and hand-eye coordination is important in giving and receiving the medication.

But what if the lighting was not or could not be optimized immediately, safely, or without undue delay? What if there was critical timing involved and more medication was needed? What if the one needing to have the medication to deliver was in a position, or positioned in such a way, so that they could not safely or conveniently get to the bottle or vial, optimized lighting or not? What if there was an immediate or emergent need for the medication and tensions were running high, making precision a little more difficult? These scenarios, and others like them, are real and do occur in many different settings.

I personally have experienced some of these situations and scenarios and I identified a potential problem: an increased risk of an accidental needle stick. In fact, I personally had suffered previous needle sticks during my medical career. The immediate and potential physical risks and complications are real and varied, as are the emotional and psychological consequences.

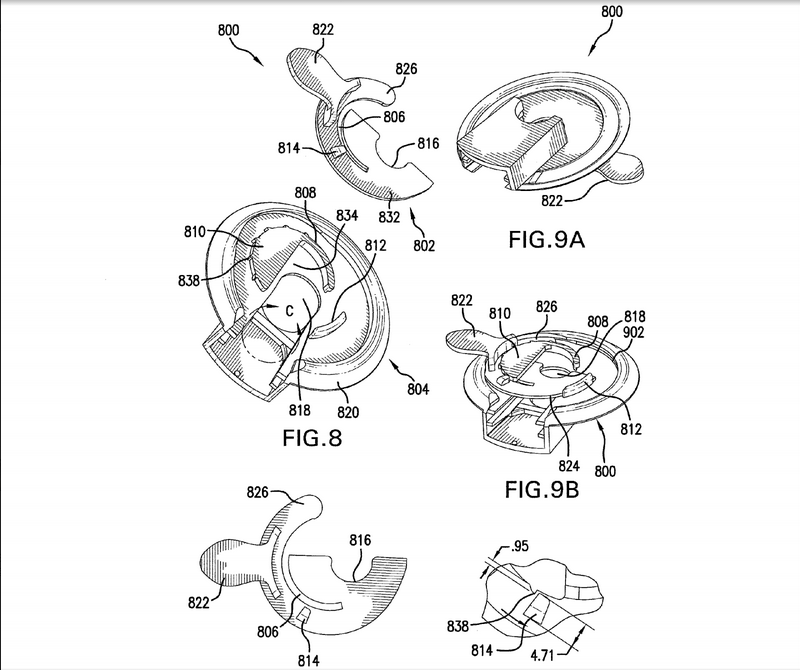

So, with a problem or challenge presenting itself on a daily basis in my work life, I began to think about it and tried to come up with a solution to the problem. It didn’t take long to think of a solution using common sense principles that many people would think of: put a physical barrier of some sort between the person holding the bottle of medication and the one holding the needle. Eureka! Of course, that was it! That might be it, but what would it look like and how would it work?

And so the journey of discovery and invention began.

Bruce Hedgepeth MD Part II of III

Bruce Hedgepeth, MD

Bruce Hedgepeth, MD

Join the conversation